Pregnant Pause: A look at ovulation, fertilization, and implantation

Posted on 2/18/15 by Courtney Smith

You know, I took a look back through all of the posts we've written over the last few years, and I noticed a glaring omission on our part. We've never once discussed pregnancy.

Part of the reason I think we've shied away from it is because everything else we talk about is equal opportunity—for the most part, everyone's body operates the same. It's only in the physiology of pregnancy and childbirth that we deviate from that. I am a firm believer, however, that knowledge can change the world, and so I think it's incredibly important that everyone—those who have the ability to have kids and those who don't—learn about pregnancy and how it changes the body.

Note: This blog post will be written using "perfect storm" circumstances. Remember: one can conceive pretty much at any time; biology isn't limited to certain weeks.

Weeks 1–2: Prime Time

When we talk about pregnancy, it's usually week to week. Seems annoyingly tedious, right? Wouldn't it be easier to keep track of things month to month? Nope!

Despite the fact that we refer to our pregnant friends and family as being "X months along," so many different things are happening week to week that there'd be far too much to fit into a monthly breakdown. In this "perfect" scenario, weeks 1 and 2 are counted even though one isn't pregnant. The first week starts on the last day of one's period.

Image captured from Human Anatomy Atlas.

Image captured from Human Anatomy Atlas.

A friend of mine once likened the body during ovulation (and the monthly cycle as a whole) to a very excited and unstable aunt. Picture it: she's painting the walls of the prospective nursery, setting up the crib, fixing decals of baby animals by the windows, and hanging a cloud mobile from the ceiling. She turns up the heat in the room and sometimes kicks the furniture a little when she gets too impatient.

Then, one of two things happens:

- The egg is fertilized! Huzzah! Our work is done.

- The egg wasn't fertilized. Well. It's time to burn the entire room to the ground.

Don't laugh. It's true. Periods are the worst.

Ovulation is the time during the cycle in which a mature egg is released from one of the ovaries and is sent down one of the fallopian tubes where it will wait to be fertilized. With the help of the hormone progesterone, the endometrium lining begins to thicken in preparation for fertilization—if the egg isn't fertilized, the lining is shed (a.k.a. burning the entire room to the ground).

Week 3: BBBBRRRRRRRMMMMMM!

You may be asking yourself, "What does that header even mean?" Well, I threw the famous Inception sound effect up there because “inception” rhymes with "conception," which is what we're going to be talking about. Inception has nothing to do with conception. Well, not really. Conception is a film that I'm writing starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt and my ovaries.

Week 3 is when conception happens. If you're wondering how that works, you're probably not old enough to be reading this.

During weeks 3 and 4, fertilization and implantation occur. Somewhere, the aunt in the nursery is throwing a party and putting the matches away, because there's going to be a baby!

When you hear “fertilize,” your mind probably goes to fertilizer, which is used to aid in the growth of plants. Fertilizer adds nutrients to help a seed grow, creating an environment perfect for the seed.

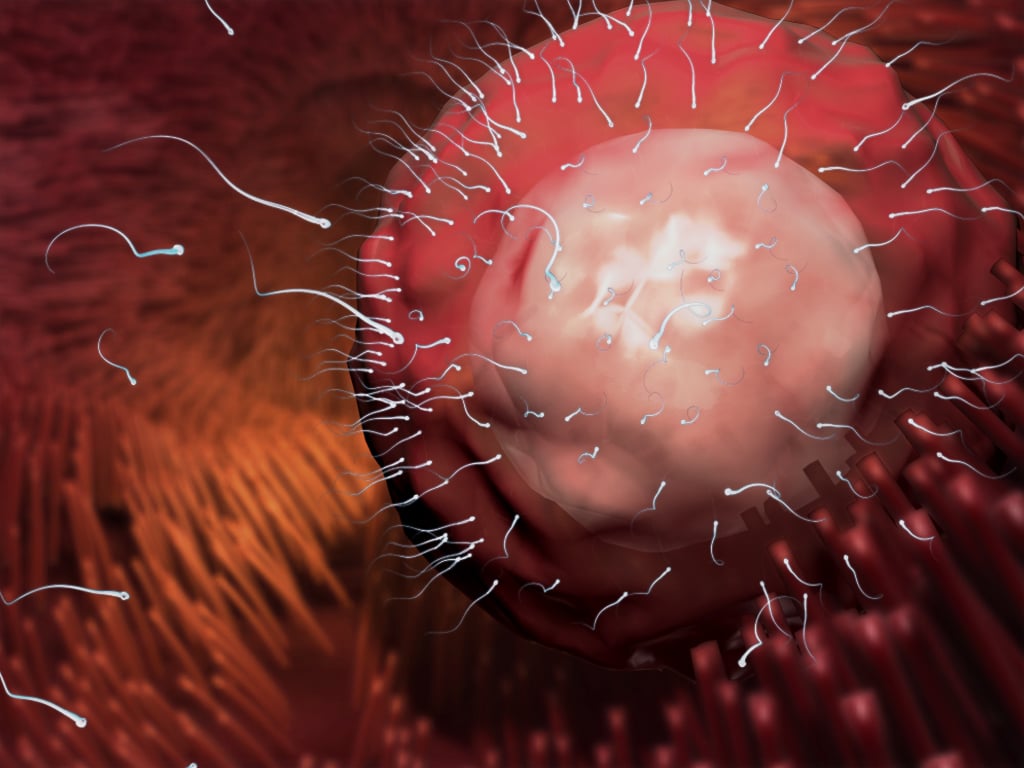

Image captured from Anatomy & Physiology.

Image captured from Anatomy & Physiology.

Fertilization is somewhat similar. Imagine an egg cell, or oocyte, is a seed. On its own, it really doesn't do much. It has the potential for life. But along comes a sperm cell, or spermatocyte, which penetrates the egg, much like the nutrients needed to kick-start the growth of a flower. The fused egg and sperm cells become a unique cell called a zygote.

Over the course of about 30 hours, the sperm cell's nucleus will fuse with that of the egg cell, combining their respective genetic material. About five days after fertilization, the zygote will divide into more cells and move down the uterus and implant into the endometrium as a collection of hundreds of cells, called a blastocyst, that continues to divide into more cells.

Week 4: Seriously, Though—

Don't Make Any Plans for the Next 9 Months

All right! Our crazy aunt is super happy and everything seems to be going swimmingly thus far. The blastocyst has implanted into the endometrium and is dividing, so now what? Well, this week marks the start of the embryonic period.

During week 4, the blastocyst will continue to divide until the cells branch into two groups: the first group includes the earliest baby cells, which will develop into the fetus, while the other group forms an environment that will protect and nourish the fetus—some of these cells will eventually develop into the placenta. When the placenta begins to develop, it sends a signal to the brain and endocrine system to start producing HCG (human chorionic gonadotropin), which is what pregnancy tests attempt to detect in blood (blood test) or urine (pee-on-a-stick test). When HCG is being produced, the body stops releasing eggs and the endometrium stays put.

However, the placenta isn't developed enough at this point to be the main provider of nutrients, so the blastocyst will be "fed" oxygen and other goodies by a microscopic circulatory system.

Stay tuned! We'll be tackling weeks 5–10 soon.

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you a professor (or know someone who is)? We have awesome visuals and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here.

Related Posts:

- Internal Female Reproductive Anatomy

- Internal Male Reproductive Anatomy

- A look at ovulation, fertilization, and implantation